Seeds of Doubt

The Tragic History and Precarious Future of the New Zealand Kauri Tree

Ko te Kauri Ko Au, Ko te Au ko Kauri

I am the kauri, the kauri is me

In Waipoua Forest, at the top of the North Island, New Zealand’s largest kauri tree stands at over 50 metres tall. According to indigenous Māori culture, it’s namesake Tane Mahuta was ‘The God of the Forest’.

As the story is told, at the beginning of the universe there was only darkness. Ranginui (the sky father) and Papatūānuku (the earth mother) lived together in a never-ending embrace, their children nestled between them away from the light.

One day, tired of the perpetual darkness, Tane decided to free himself and his siblings. Using his great strength he pushed his parents apart, forcing his father high into the heavens. Their separation allowed light to flood into the world and gave Tane dominion over the forests.

Many iwi consider the tall and ancient kauri to be the legs of Tane keeping his parents apart. Kauri are taonga and considered ancestors. They serve as sources of inspiration in songs, dances and proverbs.

For Māori the health of the forest is intrinsically linked with the health of the people. Failure to protect kauri is a failure to ensure the wellbeing of future generations.

"This is Timber Country"

- Bushman (Short Film, 1952)

The first threat to the survival of kauri was the settlement of Europeans in New Zealand and the start of the timber industry. In 1840, two-thirds of the country was covered in native bush. Kauri forest accounted for one million hectares of this land. As a species it has existed for twenty million years.

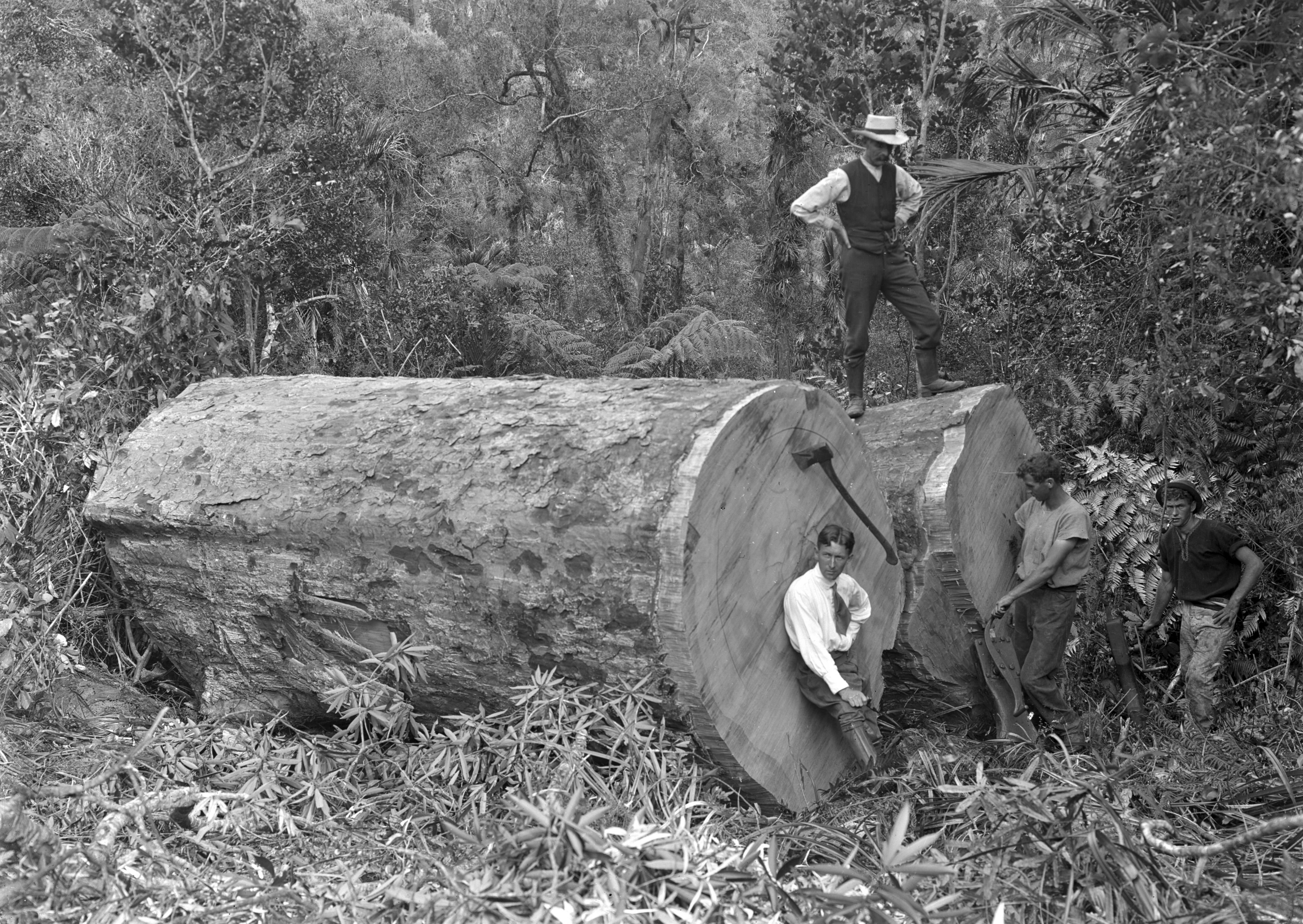

For many decades the kauri bushman has existed in the lore of New Zealand history as an icon of mateship and endurance. The gargantuan and long-lasting kauri trees stood as a worthy adversary to test the tenacity and ingenuity of these European settlers.

Kauri are believed to live as long as 1500 years, possibly even longer. The kauri felled during this time are said to have had a circumference of up to twenty-six metres - almost twice that of Tane Mahuta. In familiar black and white photos logging gangs stand together atop the felled trees, like hunters displaying their biggest trophies yet.

But while native forestry may have built the country we know today, only seven thousand hectares of kauri forest remain. The exploitation of native trees disseminated the forest ecosystems and have left kauri extremely vulnerable.

While the trees are now technically protected by the Department of Conservation, their longevity is at risk once again. This time the impending threat is proving much harder to stop than the swing of an axe.

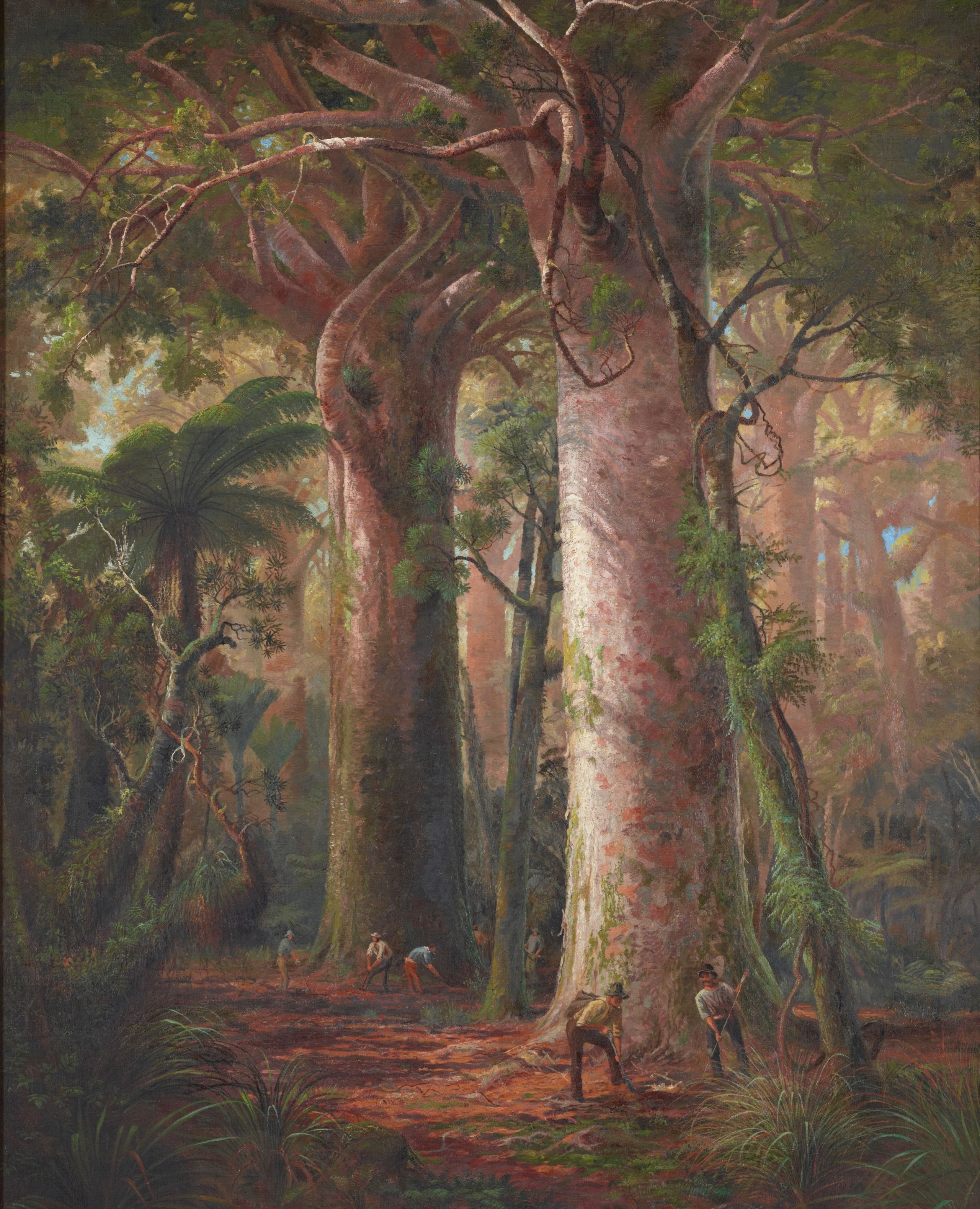

Scene of Kauri Bush, gumdiggers at work, 1892, Auckland, by Charles Blomfield. Purchased 2003. Te Papa (2004-0005-1)

Scene of Kauri Bush, gumdiggers at work, 1892, Auckland, by Charles Blomfield. Purchased 2003. Te Papa (2004-0005-1)

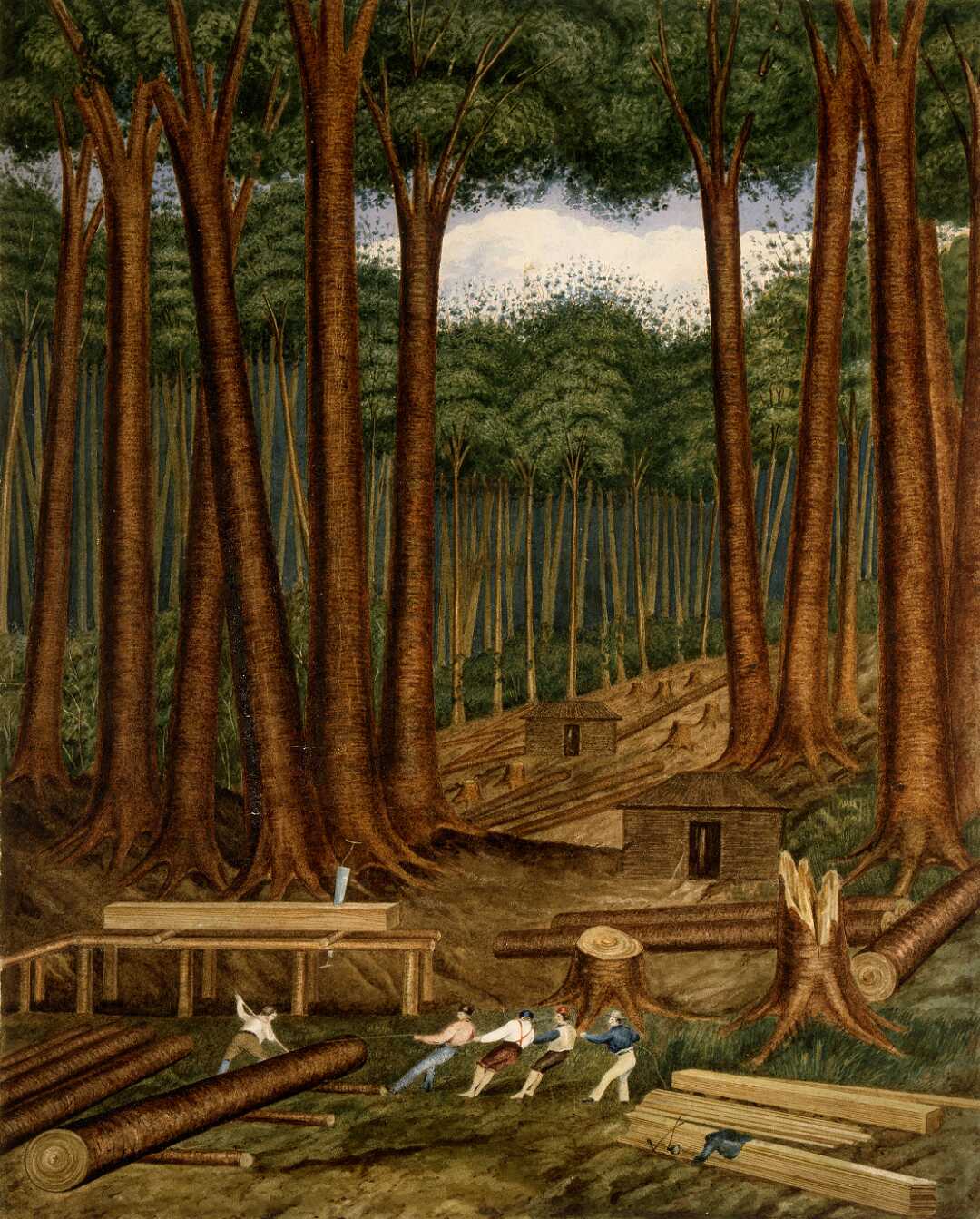

Kauri forest, Wairoa River, Kaipara. 1839, by Charles Heaphy. Ref: C-025-014. Alexander Turnbull Library. /records/22890170

Kauri forest, Wairoa River, Kaipara. 1839, by Charles Heaphy. Ref: C-025-014. Alexander Turnbull Library. /records/22890170

Phytophthora

(from Greek phytón and phthorá)

meaning: “plant-destroyer”

Excessive resin (gum) production in Kauri / Image courtesy of: https://www.kauridieback.co.nz/

Excessive resin (gum) production in Kauri / Image courtesy of: https://www.kauridieback.co.nz/

Yellowing of kauri leaves / Image courtesy of: https://www.kauridieback.co.nz/

Yellowing of kauri leaves / Image courtesy of: https://www.kauridieback.co.nz/

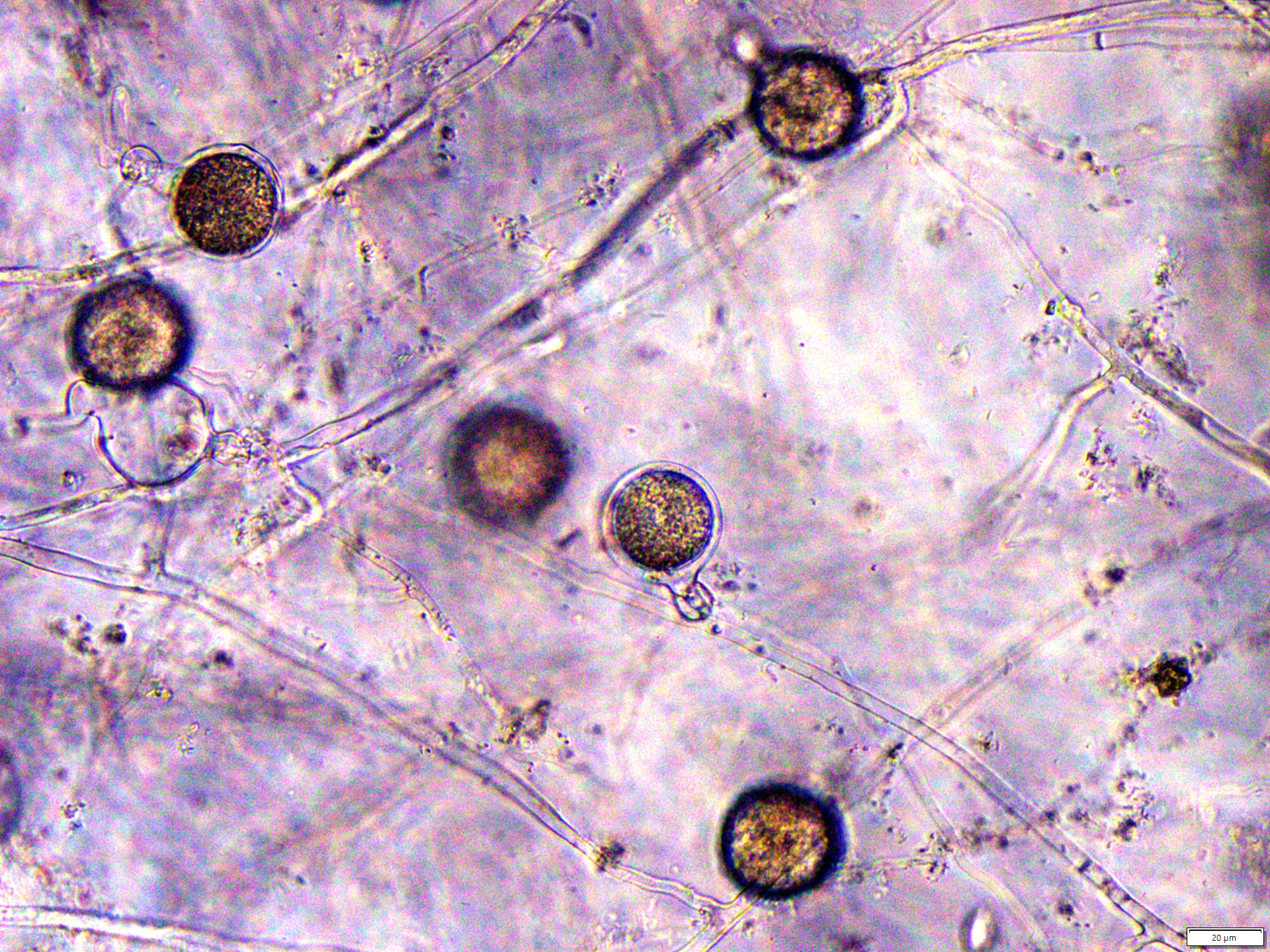

Phytophthora are a species of Oomycota, fungus-like microorganisms which are responsible for infecting a variety of different plants. One of the most well-known is phytophthora infestans, better known as potato blight, which caused the Irish Potato Famine in the 1840s.

In New Zealand, the species threatening kauri is named phytophthora agathidicida. It is the cause of the root rot disease known as kauri dieback. Initially discovered in 1972, the number of infected trees has increased over the last ten years. There is currently no known cure for infected trees and the disease is ultimately fatal for kauri.

In the initial stages of infection there are almost no visible symptoms of disease. This period can last for several years before the tree enters the chronic phase. At this point, excessive gum bleeding and the loss of the tree's crown cover are an indication that the tree is close to death. The time from infection to death is variable and can be anywhere from one to ten years, with larger trees lasting longer than their smaller, younger counterparts.

The lack of visible symptoms is perhaps the most dangerous aspect of the disease. Humans are the primary distributors of the kauri dieback. Unable to detect infected trees, any tramper or hunter who has wandered off the track has no way of knowing if any deadly microbes may have hitched a ride on their boots.

Once relocated to new soil, tiny spores are dispersed and are able to sense kauri roots and swim towards them. Moving contaminated soil to different areas can create entire new sites of infection. But it is not just individual kauri that will face elimination, p. agathidicida has the capability to destroy many other species who rely on kauri as the heart of the forest.

No one stands alone...

© Jackie Hnat

© Jackie Hnat

Kauri are a keystone species. Due to their long-life spans their leaf litter eventually changes the acidity of the soil underneath their broad canopy. This change affects the plants that grow around them and makes them critical to the forest ecosystem.

There are many species known as ‘kauri associates’ and some are epiphytes that live directly on the trunk or branches of kauri. The loss of kauri from the ecosystem is likely to result in the loss of many other species dependent on them for nutrients.

Some examples of plants at risk include the kauri greenhood orchid. Found on the forest floor, it is virtually confined to kauri due to their symbiotic relationship. Another is Kirk's tree daisy, a flowering plant which grows on kauri but is harmless to the tree.

Other plants that are endemic to kauri forests also hold additional value through their use by Māori. Mairehau is a shrub with fragrant leaves which are crushed and made into perfume. Another shrub, mingimingi, is said to hold medicinal properties and is used to treat headaches and flu symptoms. Meanwhile, toropapa produces edible fruit which is most often eaten by Kereru and other native birds.

By failing to prevent the spread of kauri dieback we put all these plants and many more at risk. The anticipated loss of kauri will have widespread cultural and ecological impacts. Without a nationwide commitment to their protection, kauri may just go the way of the Moa.

Protecting Giants

While there is no cure for kauri dieback yet, there is still hope for controlling the disease by limiting the spread.

Collaboration between central government, local government and tangata whenua has resulted in an increase in measures to prevent transmission. Three key strategies have been promoted by The Kauri Dieback Programme.

The first is the implementation of cleaning stations at the beginning of 'at risk' tracks to reduce the spread of the pathogen via footwear. The second is the construction of boardwalks on trails, such as the one leading to Tane Mahuta, to stop people from contaminating the soil at all. Lastly, several high risk tracks have been closed to the public entirely to protect kauri.

A rahui has been placed over these trails to prioritise the survival of kauri. Yet, the Auckland Council has reported that they have received complaints from members of the public who feel it is unfair to close them to walkers. In addition, several people have continued to ignore the restrictions and those caught have received trespass notices.

It is our great shame that even after the destruction of so much of our native forest there are still people who feel entitled to further endanger kauri trees. If trespass notices don’t defer people from taking to the tracks then perhaps it’s time for harsher penalties for violating these restrictions.

Kauri should be some of the oldest trees in the world. If we put in the effort they could outlive us all. Let's give them a chance. Keep kauri standing.