Green is the New Black

A critical reflection of the impacts

of the fashion industry on the planet and its

inhabitants.

Fashion: One of the World's Most Polluting Industries

jbdfbubf

lnsovbsjdbviubsd

jbebfibjdkbfe

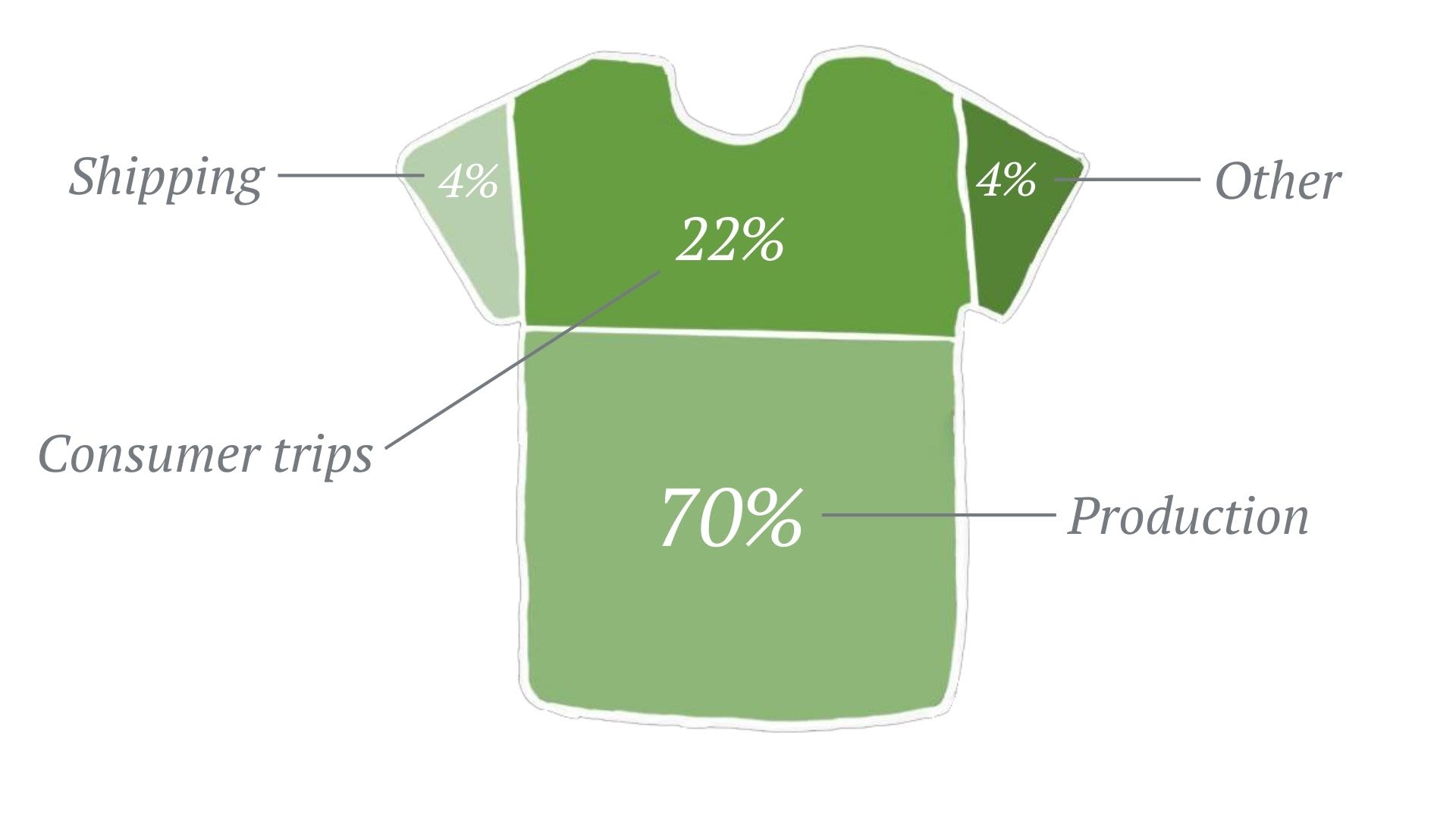

While 90% of clothing garments are shipped by containers from low and middle income countries, shipping only accounts for a small percentage of the total emissions. The large majority comes from production and a surprisingly high amount comes from consumer trips to purchase clothing.

jfiwbjisfub

Despite its pretty appearance, the fashion industry has some ugly truths.

The fashion industry is a massive contributor to environmental degradation, globally.

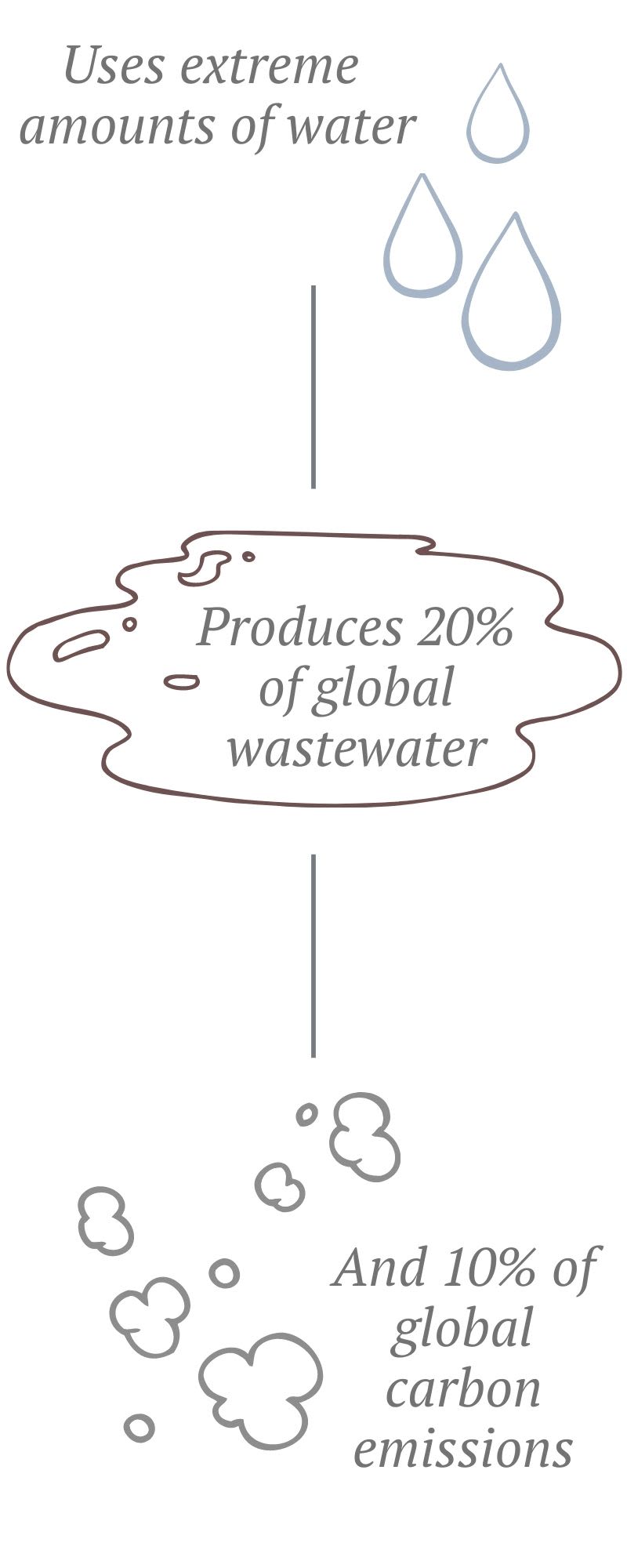

The production of clothing uses extreme amounts of water and creates 20% of global wastewater.

Additionally, the fashion industry alone produces 10% of global carbon emissions – more than all international flights and maritime combined.

jclknsdlfwlkrnlf

vrgergfvasca

Fashion Industry Carbon Emissions

"The breadth and depth of social and environmental abuses in fast fashion warrants its classification as an issue of global environmental justice."

Enemy Number 1: Polyester

Polyester: a textile that became known as a miracle fibre post-WWII for its ability to be worn for 68 days straight without ironing and still looking presentable. Today, polyester is the most widely-used manufactured fibre.

However, polyester is not as nice as it seems. Made from petroleum, it is constructed by melting and combining two types of oil-derived plastic pellet to create the polymer polyethylene teraphlalate. This process requires large amounts of crude oil, which releases harmful emissions such as volatile organic compounds, particulate matter and acid gases like hydrogen chloride, all of which can cause or worsen respiratory disease. Additionally, most polyester is made using antimony (a metalloid similar to arsenic), which is carcinogenic as well as toxic to the heart, liver and skin.

Finally, volatile monomers, solvents and other by-products are emitted into wastewater from polyester manufacturing plants. For this reason, many textile factories are now considered to be hazardous waste generators.

Enemy Number 2: Cotton

Cotton, often seen as a natural, earth-friendly fibre is also one of the most water and pesticide dependent crops when conventionally grown.

In fact, more than 10,000 litres of water is required to produce one kilogram of cotton; enough to produce one pair of blue jeans or, comparatively, the same amount a person drinks in 10 years. Globally, less than a third of cotton is rain fed. Given the vast amounts of water it requires, it is abusing a vital resource in many drought-prone areas where it is grown.

While cotton is natural, it is a fibre that is grown with an extensive amount of toxic chemicals. Endosulfan, a commonly-used insecticide, is responsible for several thousand deaths of cotton farmers and their families. A singular drop of aldicarb, a pesticide used on cotton in 26 countries, absorbed on the skin is fatal. Overall, cotton farming accounts for a quarter of all insecticides and 11% of pesticides used universally.

it's not just the planet, it's people

"Environmental justice is described as the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, colour, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies."

Garment construction employs 40 million workers worldwide. The fashion industry is a case of transferring the environmental and occupational risks associated with mass production overseas. As a result, 90% of clothing production occurs in low and middle income countries.

These are places where, due to poor political settings and institution control, occupational and safety standards are not properly enforced. Bangladesh has long been one of the cheapest places to produce clothes, where the minimum wage is 32 cents an hour (USD) or $68 a month.

The consequence is a multitude of health and safety hazards including: a higher likelihood of respiratory conditions due to poor ventilation and therefore the gathering of cotton and synthetic particles; and musculoskeletal disorders from repetitive motions and long hours. Other health impacts reported by low and middle income countries include lung disease and cancer, endocrine dysfunction, reproduction issues, unintentional injuries, injuries due to overworking and death.

Repeated occurrences of avoidable disasters offer stark reminders of the injustices faced by garment workers. The 2013 Rana Plaza Factory collapse in the Dhaka district of Bangladesh was an avoidable event that cost the lives of 1,134 garment workers and injured a further 2,500. Following the tragedy, the garment industry appeared to return to business as usual, with little change in safety standards for garment workers.

it's not just production, it's waste

"As we get closer to species degradation, to trashing our last remaining pristine wilderness, we seem hell bent on producing more and more disposable stuff – it makes no sense. Fashion should never and can never be thought of as disposable."

The principal economic model that describes modern consumption can be characterised as 'take, make and waste'.

This model also applies to fashion consumption, although consumption associated with clothes are arguably worse than most. This is because the emergence of fast fashion has resulted in the rapid production of clothing in response to the latest trends. While there used to be two recognised seasons in a year: summer and winter, fast fashion has now created an estimated 52 'micro-seasons'. Essentially, it's now mainstream now to purchase clothes every week of the year.

Fast fashion creates the perception that clothes are essentially disposable, causing over-production, over-consumption and extensive waste. Compared to 2000, more clothes are purchased but are kept half as long, while 40% are never worn. The result is the practical service life of garments being far lower than the technical service life.

Textile waste has become a major polluter in the third world, but also affects places like New Zealand. A study in 2019 found microplastics present in most samples across 29 Auckland beaches, 90% of which were fibres from clothing and packaging.

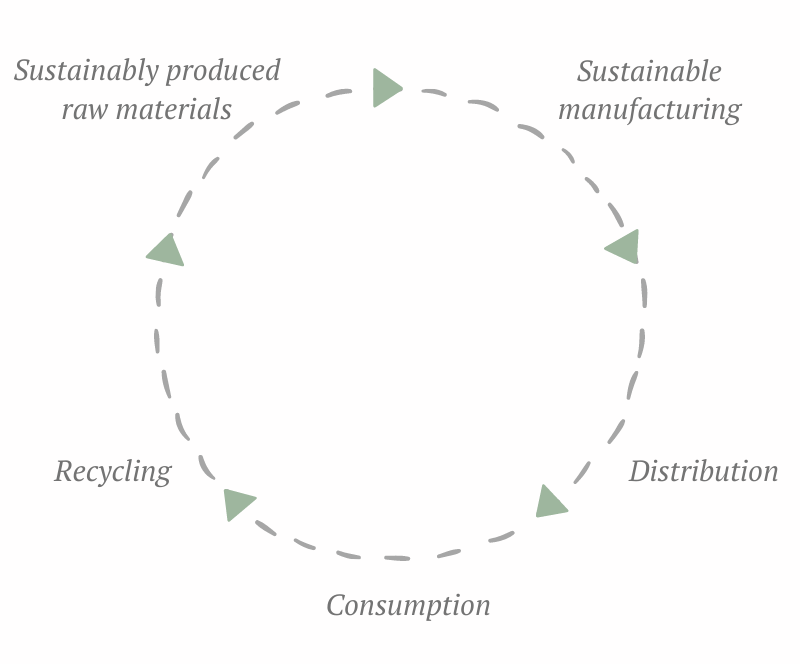

Circular Model

cshacbabdj

dsnfsjkdnknsd

If we are to take from the planet, we must give back. The ecosystem is naturally circular, from the carbon cycle to the water cycle. Even death is circular. Decomposition, which breaks apart dead plants and animals, creates nutrients in the soil that aids farmers, protects forests and helps to produce biofuels. The global fashion industry must implement a restorative and regenerative circular model, where businesses are responsible for the entire life cycle of the garments they produce, from production to disposal.

Aotearoa

"New Zealand is just on the precipice, either going the American way and just buying a lot more s***, or doing something a little differently."

Since import regulations were abolished in the 1980s in Aotearoa New Zealand, prices of all consumer goods have dropped considerably. International brands intervened and local manufacturers could no longer compete on price points, resulting in the once flourishing local industry breaking down.

While there remain a small group of New Zealand labels producing locally, cheap imported goods have won the battle of the brands. However, acquiring clothes cheaply and in large volumes only means someone else is paying for it.

In New Zealand, the main dumping ground for low-quality textile waste are op-shop and charity stores, which are being overwhelmed by the sheer quantity of clothes. As a result, large portions go to local landfills, which are rapidly reaching capacity.

In fact, Waste Management has proposed a new landfill in Dome Valley that will come to be Auckland's largest dump. Once that fills up, the rubbish gets shifted somewhere else, likely overseas for another country to deal with. Because they may take decades to centuries to degrade, these convenient short-lived purchases could have long-lasting consequences to the planet.

Solutions

"All we've got as consumers is the ability to boycott a purchase. If we all choose those eco-friendly options then brands will make more of them. They'll see it's a winning proposition."

While it may seem impossible to turn this sinking ship around, we as both consumers and citizens have real power.

We have the ability to stop the trends of mass consumption. We can stop engaging with companies that promote fast turnaround and poor treatment of garment workers; start buying vintage and secondhand; and support sustainable or local fashion brands that don't overproduce.

We have the ability to love our clothes. We can buy only the things we know we'll love for years. We can repair, mend, and cherish them. If you must get rid of a garment, make sure you give it to a charity in need of donations.

Finally we have the ability to support the larger movement. We can adjust our social networks, such as who we follow on social media, to help reinforce sustainable and circular values. We can support relevant organisations such as Mindful Fashion NZ and Fashion Revolution. We can let our policymakers know we want macro-level action taken to enhance circular functions in the local fashion sphere.

It takes just one thing to kickstart these habits, and that could be as simple as walking past a fast fashion retailer on your way through the mall.

"There should be no love for a system that uses and abuses such a joyful expression of human creativity and puts profit ahead of people and the planet."